THE MATTER OF ART AND ARTISTS

Internet publication by Bert Witkamp.

First published: 14 August 2015 as no 8 of Art in Zambia Blog series.

Current revision and update: 26 May 2024.

This internet publication serves to contribute to a better understanding of material-technical knowledge and ability with special reference to the development of modern art in Zambia.

Introduction

Western art media such as oil painting, water colour painting and the printed graphic arts were introduced in Zambia during the colonial days and thereafter by European artists (See G. Ellison, 2004). These media, from the Zambian perspective, are therefore exotic in origin. Its materials and techniques were taken up by Zambian artists, often in an incidental and piecemeal fashion. Some Zambian modern art of the early days – let us say roughly as of the 1950’s - is poor from a material-technological point of view. Also presently art made in the modern techniques does not meet, or may not do so, technical standards of the region of origin of these techniques and as applicable to art marketed and displayed as fine art; be it art made by indigenous Zambians, early European permanent residents or non-Zambian temporary residents.

The deterioration of the physical condition of the art object brings with it a deterioration of its imagery, hence of its artistic, social and economic value. Poorly made art, as far as the artistic experience is concerned, in time delivers an unintended visual sensation which in extreme cases makes sensible interpretation impossible. It matters therefore that art is made in accordance with the standards that ought to be observed in the art world of its provenance and meets the requirements of its functional social context. We expect, for example, that if a work of art is sold as fine art with a corresponding hefty price tag attached to it, that such a work of art has been made in compliance with appropriate material-technical standards and does not fade, flake or crack within a short time after its purchase. The material integrity of a work of art is optimally achieved if professional technical standards are practiced and the work is kept under proper conditions (see Witkamp, 2015). In Zambia, and elsewhere, materially poorly constructed art is presented as quality fine art, art that is likely to deteriorate in a short time and hence shall loose its function and value as a work of art. Examples are presented below.

Lack of material-technological understanding and/or appreciation in Zambia has been exacerbated by the corrosion of technical standards of the conventional western fine arts as practised in their region of origin and is perpetuated by absence of educational facilities where sound material technology of art can be accessed and practiced – be it in Western schools of art or in Zambia. Art technical handbooks are nearby impossible to get in Zambia, but in this field, as in so many others, searching the net may deliver the information that is needed.

Appended to this paper is an itinerary of simple measures that can be taken by (Zambian) artists to improve on the material construction of their art.

Art is a thing

Art is made of matter and hence has a physical existence. All art, in one way or another, is made of materials having specific physical and chemical properties. Certain physical properties provide the raw stimuli for perception - external stimuli that capture the sensors of the sensory systems. In the visual arts material properties that have to do with light are of paramount importance. Our eyes perceive the artwork by the light the work of art reflects or emits. Light, refracted by the cornea and the lens reaches the retina, located at the back of the eye ball. The retina is a highly sophisticated structure composed of nerve cells and sensors. The sensors are of two types. The cones, about seven million of them, are chromatic, i.e., sensitive to colour. The rods, of which there are about 125 million, are achromatic. The rods are much more sensitive to light than are the cones, which is why at night you see black or grey shapes but no colour. Light falling on the cones and pyramids triggers off physical/chemical reactions which in turn engage the optic nerves. The optic nerves, about one million of them, transduce information to the occipital lobes, located in the cortex at the back of the head. These lobes, one right and one left, are the visual processing centres of our brain and mind. Our brain and mind during and in perception construct the imagery associated to the artwork that is perceived. The imagery is mental and internal; the perceived object is material and external. This is a stunning fact as we are naturally inclined to think that what we see is what is out there – truth is that what we see is a transformation of what is out there in the form of imagery. Note, furthermore, that your mind’s eye is not a mechanical recording machine; it has learned to see and its seeing differs individually and cross culturally (see Arnheim, 1964).

We do not have an objective instrument to assess (“measure”) artistic merit of a work of art. The study of materials and techniques of art, however, provides a way to evaluate how well a work of art is made as an object. The assessment must be carried out in the context of the art tradition of the art under investigation, that is, of its provenance and its standards of craftmanship. A work of art when placed in an alien environment is likely to be valuated differently as in its art world of origin. This often happens when ethnographic artefacts are removed from their indigenous situation to a museum or to a private collection. In the museum measures need to be taken to preserve and conserve the object well - as that is a core thing museums must do: keep objects well, including objects that were not made to last. In the native situation the broken mask is replaced by a similar, new one and the old mask is discarded. Ironically, that old dilapidated mask is the one collectors go for, it being considered more authentic than its newly made successor.

In the Western art world great importance is attached to uniqueness and originality of art. These features contribute substantially to the financial value of the work of art. Sensible art collectors therefore prefer to buy art that is both original and well made. Such works last and do not require costly pre- or conservation measures. Much traditional (“tribal”) African art is not governed by such an ideology: the work must be functional and when it is breaking down it is replaced. There is therefore no dominating emphasis on permanence and uniqueness, permanence is achieved by reproduction. There are, however, in the African continent also immensely impressive examples of art deliberately made to last – ancient Egyptian sculpture perhaps being foremost amongst these as are many other examples of art mostly associated with kingdoms.

Art is an image

The relation between art object, perception and mental imagery of the perceived art object is complex and not the subject of this article. Suffice it here to note that seeing is something you have to learn and this also applies to the perception of art. For our present purposes we merely emphasize the intrinsic relationship between art object and percept of that object. If visual material properties of the work of art change, so does its perception and mental image. Artists and keepers of art need to know and understand the changes that shall or may occur in the art object once it has been made; be these changes issuing from the manner of its construction or of the environment in which it is kept.

Art is for the moment or for eternity

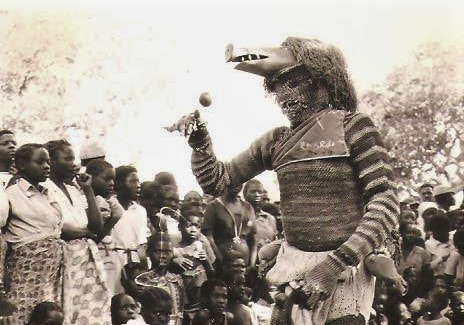

Some art is not made to last; it is made for a single occasion after which it is destroyed. Its material integrity only needs to be sustained during the event for which it has been constructed. This, for example, holds for certain makishi masks used during the boys initiation of the Luvale, Chokwe, Lunda, Luchazi and Mbunda peoples of North West Zambia. Other art is used at multiple occasions. This, for example, is true for makishi masks that have entertaining functions also outside of mukanda, the boys initiation referred to above. Examples are Mwana Pwevo (the young women) and Ngulu (the pig).

First published: 14 August 2015 as no 8 of Art in Zambia Blog series.

Current revision and update: 26 May 2024.

This internet publication serves to contribute to a better understanding of material-technical knowledge and ability with special reference to the development of modern art in Zambia.

Introduction

Western art media such as oil painting, water colour painting and the printed graphic arts were introduced in Zambia during the colonial days and thereafter by European artists (See G. Ellison, 2004). These media, from the Zambian perspective, are therefore exotic in origin. Its materials and techniques were taken up by Zambian artists, often in an incidental and piecemeal fashion. Some Zambian modern art of the early days – let us say roughly as of the 1950’s - is poor from a material-technological point of view. Also presently art made in the modern techniques does not meet, or may not do so, technical standards of the region of origin of these techniques and as applicable to art marketed and displayed as fine art; be it art made by indigenous Zambians, early European permanent residents or non-Zambian temporary residents.

The deterioration of the physical condition of the art object brings with it a deterioration of its imagery, hence of its artistic, social and economic value. Poorly made art, as far as the artistic experience is concerned, in time delivers an unintended visual sensation which in extreme cases makes sensible interpretation impossible. It matters therefore that art is made in accordance with the standards that ought to be observed in the art world of its provenance and meets the requirements of its functional social context. We expect, for example, that if a work of art is sold as fine art with a corresponding hefty price tag attached to it, that such a work of art has been made in compliance with appropriate material-technical standards and does not fade, flake or crack within a short time after its purchase. The material integrity of a work of art is optimally achieved if professional technical standards are practiced and the work is kept under proper conditions (see Witkamp, 2015). In Zambia, and elsewhere, materially poorly constructed art is presented as quality fine art, art that is likely to deteriorate in a short time and hence shall loose its function and value as a work of art. Examples are presented below.

Lack of material-technological understanding and/or appreciation in Zambia has been exacerbated by the corrosion of technical standards of the conventional western fine arts as practised in their region of origin and is perpetuated by absence of educational facilities where sound material technology of art can be accessed and practiced – be it in Western schools of art or in Zambia. Art technical handbooks are nearby impossible to get in Zambia, but in this field, as in so many others, searching the net may deliver the information that is needed.

Appended to this paper is an itinerary of simple measures that can be taken by (Zambian) artists to improve on the material construction of their art.

Art is a thing

Art is made of matter and hence has a physical existence. All art, in one way or another, is made of materials having specific physical and chemical properties. Certain physical properties provide the raw stimuli for perception - external stimuli that capture the sensors of the sensory systems. In the visual arts material properties that have to do with light are of paramount importance. Our eyes perceive the artwork by the light the work of art reflects or emits. Light, refracted by the cornea and the lens reaches the retina, located at the back of the eye ball. The retina is a highly sophisticated structure composed of nerve cells and sensors. The sensors are of two types. The cones, about seven million of them, are chromatic, i.e., sensitive to colour. The rods, of which there are about 125 million, are achromatic. The rods are much more sensitive to light than are the cones, which is why at night you see black or grey shapes but no colour. Light falling on the cones and pyramids triggers off physical/chemical reactions which in turn engage the optic nerves. The optic nerves, about one million of them, transduce information to the occipital lobes, located in the cortex at the back of the head. These lobes, one right and one left, are the visual processing centres of our brain and mind. Our brain and mind during and in perception construct the imagery associated to the artwork that is perceived. The imagery is mental and internal; the perceived object is material and external. This is a stunning fact as we are naturally inclined to think that what we see is what is out there – truth is that what we see is a transformation of what is out there in the form of imagery. Note, furthermore, that your mind’s eye is not a mechanical recording machine; it has learned to see and its seeing differs individually and cross culturally (see Arnheim, 1964).

We do not have an objective instrument to assess (“measure”) artistic merit of a work of art. The study of materials and techniques of art, however, provides a way to evaluate how well a work of art is made as an object. The assessment must be carried out in the context of the art tradition of the art under investigation, that is, of its provenance and its standards of craftmanship. A work of art when placed in an alien environment is likely to be valuated differently as in its art world of origin. This often happens when ethnographic artefacts are removed from their indigenous situation to a museum or to a private collection. In the museum measures need to be taken to preserve and conserve the object well - as that is a core thing museums must do: keep objects well, including objects that were not made to last. In the native situation the broken mask is replaced by a similar, new one and the old mask is discarded. Ironically, that old dilapidated mask is the one collectors go for, it being considered more authentic than its newly made successor.

In the Western art world great importance is attached to uniqueness and originality of art. These features contribute substantially to the financial value of the work of art. Sensible art collectors therefore prefer to buy art that is both original and well made. Such works last and do not require costly pre- or conservation measures. Much traditional (“tribal”) African art is not governed by such an ideology: the work must be functional and when it is breaking down it is replaced. There is therefore no dominating emphasis on permanence and uniqueness, permanence is achieved by reproduction. There are, however, in the African continent also immensely impressive examples of art deliberately made to last – ancient Egyptian sculpture perhaps being foremost amongst these as are many other examples of art mostly associated with kingdoms.

Art is an image

The relation between art object, perception and mental imagery of the perceived art object is complex and not the subject of this article. Suffice it here to note that seeing is something you have to learn and this also applies to the perception of art. For our present purposes we merely emphasize the intrinsic relationship between art object and percept of that object. If visual material properties of the work of art change, so does its perception and mental image. Artists and keepers of art need to know and understand the changes that shall or may occur in the art object once it has been made; be these changes issuing from the manner of its construction or of the environment in which it is kept.

Art is for the moment or for eternity

Some art is not made to last; it is made for a single occasion after which it is destroyed. Its material integrity only needs to be sustained during the event for which it has been constructed. This, for example, holds for certain makishi masks used during the boys initiation of the Luvale, Chokwe, Lunda, Luchazi and Mbunda peoples of North West Zambia. Other art is used at multiple occasions. This, for example, is true for makishi masks that have entertaining functions also outside of mukanda, the boys initiation referred to above. Examples are Mwana Pwevo (the young women) and Ngulu (the pig).

These “entertainment” masks are made of wood, wood being more permanent than masks made of bark cloth, hessian or other fabric. The worn-down mask is disposed off and replaced by a new one according traditional rules and models.

Some art is made to last to eternity. Egyptian sculptures dating back to the earliest times of the pharaohs, some 5,000 years ago, belong to this group. Today many of those ancient sculptures look the same or nearly the same as at the time of their creation, thousands of years ago.

In conclusion: technology is directed by functionality and ideology. It is realised by the means at hand, which, as archaeological and historical evidence abundantly show, might come from far away.

Material technology is part of an art tradition, an art tradition is part of an art world.

Art, no matter where or when, is embedded in a larger context. We can name that larger context an art tradition, or more broadly, an art world. For the time being, let us stick to the concept “art tradition.” The term tradition implies a customary way of doing things and “a customary way of doing things” implies historical depth. Each art tradition has its specific material technology; a technology that has evolved over time and is part of the culture and cultural heritage of the people having that tradition.

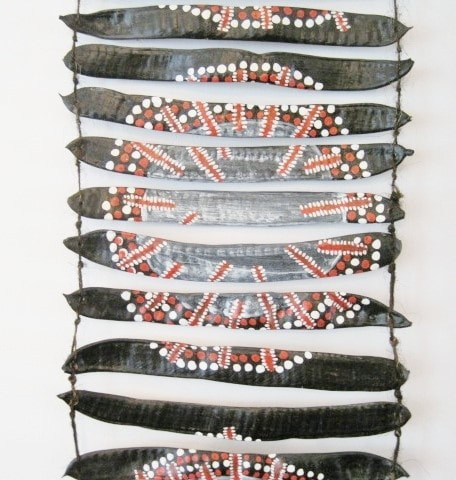

Art traditions are practiced by specific populations; the art tradition being part of the culture and cultural heritage of its associated social group, ethnicity or cluster of (related) ethnicities. The makishi tradition mentioned above belongs to a group of culturally related peoples, sometimes referred to as the West Central Bantu.

Art traditions vary tremendously and so do the materials and the technologies used in art production. Many factors influence or determine the choice of materials and their processing. These include: availability of raw materials and of processed, readymade art materials; the cost and labour of acquiring these materials; the technology/science to process raw materials into finished products and the skills to do so; chemical inertness towards other materials the art work is made off; desirable properties concerning visual appearance such as hue, brightness, texture, transparency or opaqueness; handling qualities; the functionality of the work of art; values and requirements regards permanence or durability; or the incorporation of certain colours and materials for symbolic or metaphysical reasons. Each art tradition in the course of time developed and develops its own material technology, the skills that go with it and the standards for the assessment of its application.

Technologies do change in the course of time. New materials are incorporated into the existing stock; methods of processing these materials may change as well as the manner of their application. Yet these innovations rarely radically change the prevailing traditional technology - but they do modify it. The colour red of makishi masks historically was procured by red ochre (ground haematite or purified red clay; the colouring principle of both substances is red oxide of iron). For many decades red cloth, red paper or red commercial paint have replaced the original material. In this instance the important element was not the raw material as such but the colour red. That colour has been retained in this technological change, and brighter than it used to be. An example of diffusion in the western history of art is the replacement of tempera painting by (linseed) oil painting. This was an Italian innovation. Oil painting became the main painting medium in Italy during the sixteenth century A.D. and was adopted in the course of the seventeenth century throughout Europe to become the major and most prestigious painting technique for mobile paintings. The innovation was followed by diffusion, placed in a broadly defined European fine art tradition.

Art technologies not only develop in time – they also may die out. Rock art as a practice, in Zambia, presently is extinct and so is its technology. But hundreds of historical artefacts are testimonies to the importance it once had.

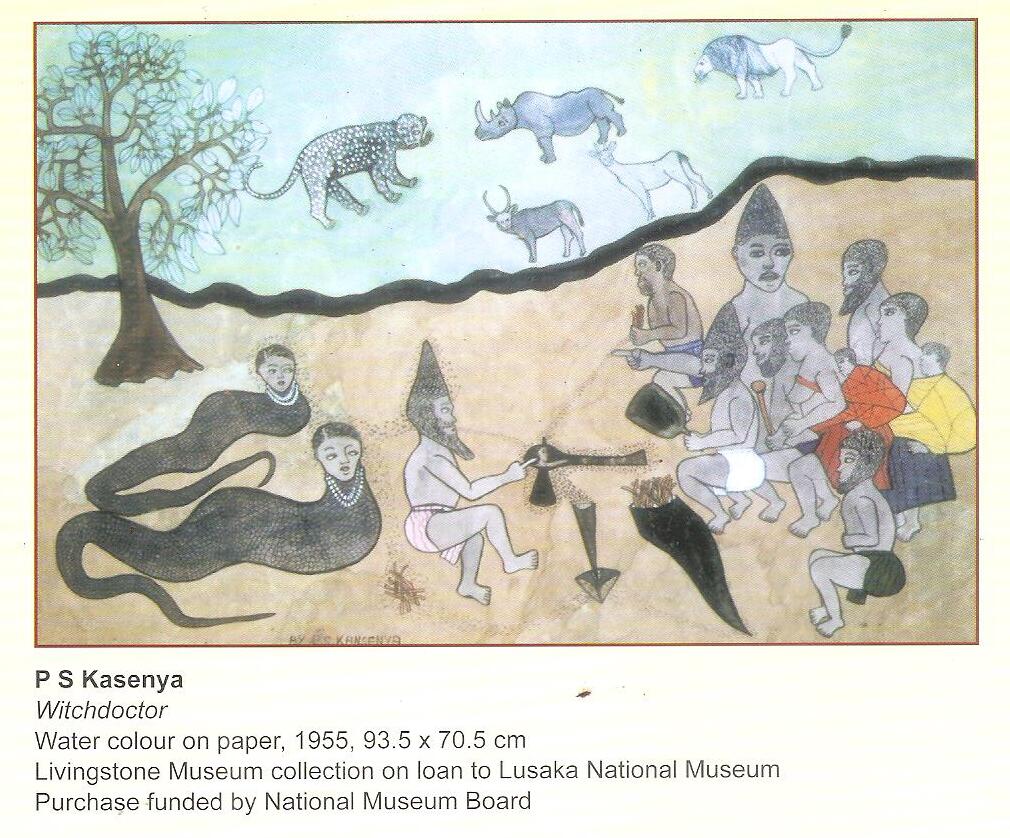

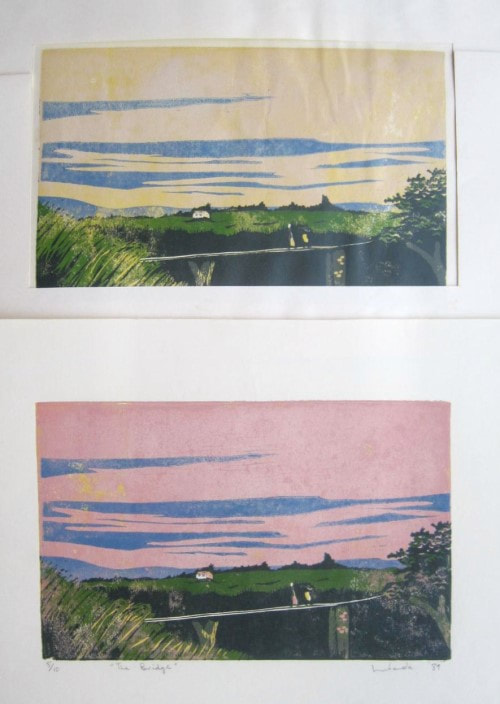

It does also happen, however, that art technologies spread from their country of origin to new lands. The introduction of the graphic arts or oil painting in Zambia is an example of such a radical innovation. The geographic diffusion of these techniques at first was restricted to the colonial subsection of the population of what then was Northern Rhodesia – for them these technologies were not new but part of the existing material culture. The geographic spread of these technologies engendered the gradual diffusion of these media throughout the population, especially after Independence in 1964 to an art scene now dominated by indigenous Zambian artists. Below an interesting, early example of the use of water coulour by a Zambian artist in the colonial days.

Some art is made to last to eternity. Egyptian sculptures dating back to the earliest times of the pharaohs, some 5,000 years ago, belong to this group. Today many of those ancient sculptures look the same or nearly the same as at the time of their creation, thousands of years ago.

In conclusion: technology is directed by functionality and ideology. It is realised by the means at hand, which, as archaeological and historical evidence abundantly show, might come from far away.

Material technology is part of an art tradition, an art tradition is part of an art world.

Art, no matter where or when, is embedded in a larger context. We can name that larger context an art tradition, or more broadly, an art world. For the time being, let us stick to the concept “art tradition.” The term tradition implies a customary way of doing things and “a customary way of doing things” implies historical depth. Each art tradition has its specific material technology; a technology that has evolved over time and is part of the culture and cultural heritage of the people having that tradition.

Art traditions are practiced by specific populations; the art tradition being part of the culture and cultural heritage of its associated social group, ethnicity or cluster of (related) ethnicities. The makishi tradition mentioned above belongs to a group of culturally related peoples, sometimes referred to as the West Central Bantu.

Art traditions vary tremendously and so do the materials and the technologies used in art production. Many factors influence or determine the choice of materials and their processing. These include: availability of raw materials and of processed, readymade art materials; the cost and labour of acquiring these materials; the technology/science to process raw materials into finished products and the skills to do so; chemical inertness towards other materials the art work is made off; desirable properties concerning visual appearance such as hue, brightness, texture, transparency or opaqueness; handling qualities; the functionality of the work of art; values and requirements regards permanence or durability; or the incorporation of certain colours and materials for symbolic or metaphysical reasons. Each art tradition in the course of time developed and develops its own material technology, the skills that go with it and the standards for the assessment of its application.

Technologies do change in the course of time. New materials are incorporated into the existing stock; methods of processing these materials may change as well as the manner of their application. Yet these innovations rarely radically change the prevailing traditional technology - but they do modify it. The colour red of makishi masks historically was procured by red ochre (ground haematite or purified red clay; the colouring principle of both substances is red oxide of iron). For many decades red cloth, red paper or red commercial paint have replaced the original material. In this instance the important element was not the raw material as such but the colour red. That colour has been retained in this technological change, and brighter than it used to be. An example of diffusion in the western history of art is the replacement of tempera painting by (linseed) oil painting. This was an Italian innovation. Oil painting became the main painting medium in Italy during the sixteenth century A.D. and was adopted in the course of the seventeenth century throughout Europe to become the major and most prestigious painting technique for mobile paintings. The innovation was followed by diffusion, placed in a broadly defined European fine art tradition.

Art technologies not only develop in time – they also may die out. Rock art as a practice, in Zambia, presently is extinct and so is its technology. But hundreds of historical artefacts are testimonies to the importance it once had.

It does also happen, however, that art technologies spread from their country of origin to new lands. The introduction of the graphic arts or oil painting in Zambia is an example of such a radical innovation. The geographic diffusion of these techniques at first was restricted to the colonial subsection of the population of what then was Northern Rhodesia – for them these technologies were not new but part of the existing material culture. The geographic spread of these technologies engendered the gradual diffusion of these media throughout the population, especially after Independence in 1964 to an art scene now dominated by indigenous Zambian artists. Below an interesting, early example of the use of water coulour by a Zambian artist in the colonial days.

A full appreciation of these material technological developments requires understanding the social setting in which these developments occurred. Firstly, that of colonial Northern Rhodesia which rendered these media a certain prestige as part of the culture of the dominating power. Secondly, and co-existent with the colonial setting until 1964, that of the emergence of towns and urban culture where these media were produced and distributed. One may note that today (2024) the Zambian modern art world is vibrant in terms of production, mostly by indigenous Zambian artists. Yet much work remains to be done to arrive at a well-developed art world; especially in education, research, media coverage, ideology, art history, marketing/promotion and museum development.

ART and art

In the Western tradition the concept “art” embraces both the ability of the artist to handle his/her materials well (art as craft or skill) and the objects made by the successful applying of these skills: ART in capitals. The double meaning of “art” reflects the understanding that an artist needs to master the skills of handling art materials and of design in order to make ART. One reason why works of art stand out from ordinary objects is because professional art is (should be) made with technical mastery. This principle is universally understood but has eroded in the 20th century Western art world by the adoption of art styles or modes of production that require very little material-technical skills, or in which the material properties of art materials simply are ignored in favour of “spontaneous expression,” are deemed irrelevant or deliberately flouted and revolted against. Any artist worldwide, however, traditionally could only become an artist after having learned the craft of his trade. Such learning was done by apprenticeship under a master and/or by studying at an Art School. See for example Warren L. d’Azevedo (1989) on the traditional artist in African societies.

I subscribe to the view that craftsmanship is basic to artistic competence and one aspect of craftsmanship is mastery of materials and techniques used in art. Some academic writers even hold that aesthetic merit arises out of technical mastery. The great Franz Boas, one of the founding fathers of modern anthropology and the first to write a book about what now usually is referred to as tribal art, holds that technical perfection creates beautiful forms, forms that turn on the aesthetic attitude (1955: 10-12), art making ART. Technical mastery, when applied, results in perfect form, pleasing surfaces and beautiful decorative patterns; formal qualities which, in his view, turn an object into ART. Boas stresses that technical mastery implies the ability to make an object “automatically,” meaning the manual operations are highly skilled and should not be inhibited by self-conscious thinking.

The deterioration of the value attached to craftsmanship in art in the West is reflected in the curriculum of Western Art Academies – the subject may or may not be taught. Consequently contemporary Western artists may have very little material understanding of the art work they produce. Similarly other major players such as galleries, museums, art critics or collectors may lack material expertise even when such should be required. After all, one does not in the Western art tradition purchase a painting to see the paint flake off its surface within a few years.

African art students attending Western art academies or fine art departments of universities similarly may not, or poorly, be taught the material technology of art - depending on the school’s curriculum and expertise.

Modern visual art in Zambia

Let me now turn to the situation in Zambia. As written above we need to bear in mind that modern easel painting, murals and graphics as fine or visual arts were introduced in Zambia during the colonial days and thereafter. These arts initially had no indigenous material history that could have guided the handling of the materials used in these arts by Zambian artists. Only in wood carving and ceramics can we establish a link between traditional and modern art applications. Today we have a modern art history several generations deep. A number of artists have developed good or even excellent craftsmanship – as a class this applies especially to the sculptors. The situation in the two dimensional arts – mostly painting and graphic art – varies from obvious ignorance to make do with what is available to a conscious attempt to use the best materials in a proper manner – that is: to abide by genuine standards in the making of fine art.

ART and art

In the Western tradition the concept “art” embraces both the ability of the artist to handle his/her materials well (art as craft or skill) and the objects made by the successful applying of these skills: ART in capitals. The double meaning of “art” reflects the understanding that an artist needs to master the skills of handling art materials and of design in order to make ART. One reason why works of art stand out from ordinary objects is because professional art is (should be) made with technical mastery. This principle is universally understood but has eroded in the 20th century Western art world by the adoption of art styles or modes of production that require very little material-technical skills, or in which the material properties of art materials simply are ignored in favour of “spontaneous expression,” are deemed irrelevant or deliberately flouted and revolted against. Any artist worldwide, however, traditionally could only become an artist after having learned the craft of his trade. Such learning was done by apprenticeship under a master and/or by studying at an Art School. See for example Warren L. d’Azevedo (1989) on the traditional artist in African societies.

I subscribe to the view that craftsmanship is basic to artistic competence and one aspect of craftsmanship is mastery of materials and techniques used in art. Some academic writers even hold that aesthetic merit arises out of technical mastery. The great Franz Boas, one of the founding fathers of modern anthropology and the first to write a book about what now usually is referred to as tribal art, holds that technical perfection creates beautiful forms, forms that turn on the aesthetic attitude (1955: 10-12), art making ART. Technical mastery, when applied, results in perfect form, pleasing surfaces and beautiful decorative patterns; formal qualities which, in his view, turn an object into ART. Boas stresses that technical mastery implies the ability to make an object “automatically,” meaning the manual operations are highly skilled and should not be inhibited by self-conscious thinking.

The deterioration of the value attached to craftsmanship in art in the West is reflected in the curriculum of Western Art Academies – the subject may or may not be taught. Consequently contemporary Western artists may have very little material understanding of the art work they produce. Similarly other major players such as galleries, museums, art critics or collectors may lack material expertise even when such should be required. After all, one does not in the Western art tradition purchase a painting to see the paint flake off its surface within a few years.

African art students attending Western art academies or fine art departments of universities similarly may not, or poorly, be taught the material technology of art - depending on the school’s curriculum and expertise.

Modern visual art in Zambia

Let me now turn to the situation in Zambia. As written above we need to bear in mind that modern easel painting, murals and graphics as fine or visual arts were introduced in Zambia during the colonial days and thereafter. These arts initially had no indigenous material history that could have guided the handling of the materials used in these arts by Zambian artists. Only in wood carving and ceramics can we establish a link between traditional and modern art applications. Today we have a modern art history several generations deep. A number of artists have developed good or even excellent craftsmanship – as a class this applies especially to the sculptors. The situation in the two dimensional arts – mostly painting and graphic art – varies from obvious ignorance to make do with what is available to a conscious attempt to use the best materials in a proper manner – that is: to abide by genuine standards in the making of fine art.

Generally, however, there is considerable room for improvement, particularly concerning the awareness of the effect of the material construction of a work of art on its perception and life span.

The introduction of “fine art” in Zambia is well described by Gabriel Ellison in her book Art in Zambia (2004: 17-24). The introduction took place in a specific segment of society; that of European expatriates, residents and settlers who, in a colonial society, constituted a subculture in which “art” testified to the presence of some sense of civilisation, their civilisation that is, inevitably associated with the upper stratum of society. Many of these pioneering artists were members of the Lusaka Art Society, established in 1947. Their art work fitted into a tradition they considered their own and that included, in varying degrees, technological awareness and competence.

Several of its prominent members in the course of time worked with or supported indigenous African artists thus setting into motion a process of diffusion of art techniques from one population to another. On the European side as of the later sixties Gabriel Ellison, Cynthia Zukas and Bente Lorenz have played major constructive roles in the formative years of fine art in Zambia including the provision of substantial support for African artists and artisans.

Major Zambian artists of the first post-Independence hour Tayali and Simpasa worked with (and under) Gabriel Ellison at the Government Graphic Art Department in Lusaka. The establishment of the Art Teachers Diploma Course at the Evelyn Hone College later in the 1960’s was another milestone in the dissemination of Western art techniques. Initially most lecturers were Europeans who gradually were replaced by Zambians who had graduated from the college and/or had enjoyed a western style art education elsewhere. The Evelyn Hone College was to become a major provider of Zambian artists. So was, in a minor way, the Mindolo Oecumenical Centre at Ndola and, more recently, the Art Department of The Open University at Lusaka. Technology has not been taught as a separate subject in these institutions, save for a brief spell (1977-1980) when the writer of this paper lectured in materials and techniques of art at the Evelyn Hone College. The prime objective of that course was to introduce the students to a number of basic principles in art technology with the specific aim of enabling them to make art materials for art classes at secondary schools using locally available raw materials – this is at a time when there were no art educational supplies in Zambia due to strict foreign currency regulations.

The most prestigious avenue of exposure of Zambian art students to western fine art technology was and is by study abroad.

The introduction of “fine art” in Zambia is well described by Gabriel Ellison in her book Art in Zambia (2004: 17-24). The introduction took place in a specific segment of society; that of European expatriates, residents and settlers who, in a colonial society, constituted a subculture in which “art” testified to the presence of some sense of civilisation, their civilisation that is, inevitably associated with the upper stratum of society. Many of these pioneering artists were members of the Lusaka Art Society, established in 1947. Their art work fitted into a tradition they considered their own and that included, in varying degrees, technological awareness and competence.

Several of its prominent members in the course of time worked with or supported indigenous African artists thus setting into motion a process of diffusion of art techniques from one population to another. On the European side as of the later sixties Gabriel Ellison, Cynthia Zukas and Bente Lorenz have played major constructive roles in the formative years of fine art in Zambia including the provision of substantial support for African artists and artisans.

Major Zambian artists of the first post-Independence hour Tayali and Simpasa worked with (and under) Gabriel Ellison at the Government Graphic Art Department in Lusaka. The establishment of the Art Teachers Diploma Course at the Evelyn Hone College later in the 1960’s was another milestone in the dissemination of Western art techniques. Initially most lecturers were Europeans who gradually were replaced by Zambians who had graduated from the college and/or had enjoyed a western style art education elsewhere. The Evelyn Hone College was to become a major provider of Zambian artists. So was, in a minor way, the Mindolo Oecumenical Centre at Ndola and, more recently, the Art Department of The Open University at Lusaka. Technology has not been taught as a separate subject in these institutions, save for a brief spell (1977-1980) when the writer of this paper lectured in materials and techniques of art at the Evelyn Hone College. The prime objective of that course was to introduce the students to a number of basic principles in art technology with the specific aim of enabling them to make art materials for art classes at secondary schools using locally available raw materials – this is at a time when there were no art educational supplies in Zambia due to strict foreign currency regulations.

The most prestigious avenue of exposure of Zambian art students to western fine art technology was and is by study abroad.

As of Independence till the present a good number of Zambian artists have benefitted from tertiary studies abroad, including the first major post-Independence artists. Aquila Simpasa and Henry Tayali as well as lesser known others such as Mwimanji Chellah and Billy Nkunika enjoyed academic education. The technical competence of the graduates of these foreign art schools or university departments varied and varies considerably due to reasons stated above. Consequently the fine art enclave of a broadly defined Zambian art world still in cases scores poorly on its mastery of material technology – though positively notable professional competence in both 2- and 3-dimensional divisions must be acknowledged.

Note that presently access to art technological information is easier than ever and no longer requires formal education. All that is required is to surf the net by smart phone or computer.

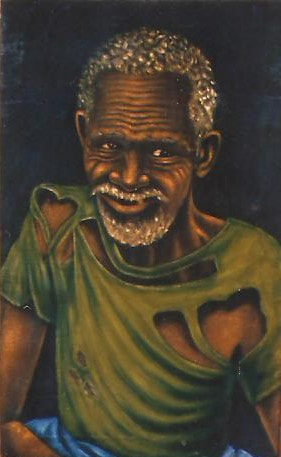

Ellison (2004: 17), to her credit, mentions another entry in Zambia of art technologies practiced by Congolese who often had been instructed by European teachers. Congolese artists had become internationally recognised as of the fifties and a number of them made a living in prosperous and peaceful Zambia of the sixties. In the seventies they constituted the largest single group of artists in Lusaka, doing oil painting and murals. They were known for their velvet paintings and heavy impasto works.

Note that presently access to art technological information is easier than ever and no longer requires formal education. All that is required is to surf the net by smart phone or computer.

Ellison (2004: 17), to her credit, mentions another entry in Zambia of art technologies practiced by Congolese who often had been instructed by European teachers. Congolese artists had become internationally recognised as of the fifties and a number of them made a living in prosperous and peaceful Zambia of the sixties. In the seventies they constituted the largest single group of artists in Lusaka, doing oil painting and murals. They were known for their velvet paintings and heavy impasto works.

The Congolese artists delivered a major input in the emergence of popular art, indeed art for the so-called common folk as well as for the upcoming Zambian middle and upper class; as opposed to the sophisticated fine arts for the educated elite. As Ellison writes, several Zambian artists picked up the Congolese styles. Many well trained Congolese artists, lacking proper art materials in Zambia, resorted to a manner of making do with what is available was and adopted a McGyvering of technology still persisting today. Its outstanding feature is the use of a wooden, non-adjustable frame, on which cotton cloth is stretched as support to be painted with white pva serving as a ground.

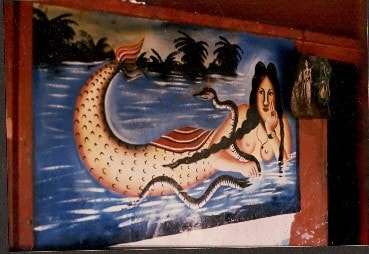

The Congolese easel painters targeted a wide market of both Europeans (mostly expatriates and tourists) and Zambians (mostly lower middle class and higher). The Congolese muralists, painting in bars and shops, worked for a near exclusive African audience in the sixties and seventies. Some of these murals rank as genuine folk art, examples are/were the paintings at the Moonlight bar on Palabana Road just out of Lusaka and other bars. Presently such work now often is deteriorated or destroyed.

The Congolese easel painters targeted a wide market of both Europeans (mostly expatriates and tourists) and Zambians (mostly lower middle class and higher). The Congolese muralists, painting in bars and shops, worked for a near exclusive African audience in the sixties and seventies. Some of these murals rank as genuine folk art, examples are/were the paintings at the Moonlight bar on Palabana Road just out of Lusaka and other bars. Presently such work now often is deteriorated or destroyed.

The murals were made using commercial paints on ordinary walls without any provision for their conservation. Zambian commercial artists as of the eighties replaced the Congolese who gradually disappeared out of the scene along with Zambia’s now declining economy.

The Zambian art world, historically, therefore, is not one of a kind but composed of several strands, the modern visual arts being only one of them. Historically first is what we may call the visual arts of traditional society, usually referred to as tribal arts. Its masking traditions are the most striking as far as imagery is concerned. In this tradition are a large variety of decorative arts, applied on pottery or basketry and other utility objects, bead work mostly as part of the human costume and in some locations decorations of shelters and huts. This broad array of products is made by technologies handed down generation after generation in a dominantly rural environment. Most people lived in villages some larger, some smaller, and incidentally in larger settlements. These tribal arts and crafts historically are the origin of the Zambian art world. At the opposite side of the spectrum are the modern visual arts. Predominantly urban, of relatively recent introduction, largely exotic in origin and addressing only a small section of the population. Bridges between the old and new concerning materials are mainly in sculpture and ceramics.

The Zambian art world, historically, therefore, is not one of a kind but composed of several strands, the modern visual arts being only one of them. Historically first is what we may call the visual arts of traditional society, usually referred to as tribal arts. Its masking traditions are the most striking as far as imagery is concerned. In this tradition are a large variety of decorative arts, applied on pottery or basketry and other utility objects, bead work mostly as part of the human costume and in some locations decorations of shelters and huts. This broad array of products is made by technologies handed down generation after generation in a dominantly rural environment. Most people lived in villages some larger, some smaller, and incidentally in larger settlements. These tribal arts and crafts historically are the origin of the Zambian art world. At the opposite side of the spectrum are the modern visual arts. Predominantly urban, of relatively recent introduction, largely exotic in origin and addressing only a small section of the population. Bridges between the old and new concerning materials are mainly in sculpture and ceramics.

In between the historical original and the exotic modern stands popular art. Emerging in the fifties and sixties, mostly done as painting, also exotic in origin, yet explicitly African: drawing on mythology, folklore and rural or urban life experiences, be these romanticised images of village life or the realities of modernity. The first documented Zambian art is of the fifties and would mostly be classed as folk art. During the sixties and seventies Congolese artists, in terms of quantity and popularity, dominated the Lusaka art scene. They introduced a variety of popular arts varying from tourist art, to realistic velvet paintings, to well-made landscapes, cubist imagery, modern life scenes to folklore. When the Congolese disappeared from the scene Zambia artists have come to fill their place making art that has in common that both imagery and what the imagery is about are readily grasped. Some of it would classify as folk art, we also see idealised stereotypical village scenes and imagery depicting urban life. Generally this art appeals to the public at large, offering no difficulty in finding out what the imagery is or what it is about; oscillating between the superficiality of kitsch and the sophistication of true fine art. In this spectrum is the remarkable emergence of portraiture, often by self-taught artist working in pencil on paper. Zambia has a good number of excellent portraitists in terms of technical skill and (hyper) realist representation. This kind of art is supposed to take the viewer in by its extraordinary manner of execution. On the down side: often the stress is on realistic representation and not on the portrayal of character.

Conclusion

Above I have emphasized that mastery of materials and techniques is important especially if the material integrity of a work of art is to extend in time – meaning that the change in its visual appearance in time should be as minor as possible. I also have noted that art materials and techniques are a cultural trait belonging to a specific art tradition. The dissemination or diffusion of western art technology in Zambia occurred piecemeal and haphazard, often resulting in poor material craftsmanship – notably of 2-dimensional art. This state of affairs has been exacerbated because of deteriorating standards in Western fine art itself as regards material competence and deficiencies in the emerging Zambian modern art world, particularly in education.

Improvement in material technical skills notably in the 2-dimensional modern arts in Zambia can be achieved if artists are more knowledgeable in this matter. Such requires the teaching and practicing of material technology at the various tertiary art educational facilities, notably the Evelyn Hone art teachers diploma course and the Open University Art Department. Such courses should start off with the Zambian material cultural heritage and next move on to technologies introduced into Zambia during the colonial days and thereafter. Zambian art education generally should start with the Zambian/African heritage rather than focus on manners of art production current elsewhere. This can only happen if the teachers of these schools are well versed in traditional material technologies including bead work, pottery, weaving and wood work. In this regard there is also for the five Zambian national museums a great and challenging task.

Appendix 1. Simple ways to improve material-technical competence

To improve on the material technology of art artists should not only consider their work of art as a creative statement but also as a work of construction. Imagine you order a dining table from a carpenter and pay the proper price for it. If such a table collapses within a short time or develops wobbling legs you complain. In art the situation is similar: As a professional you offer a product for sale and that object therefore must be made according to professional standards of workmanship. I add here that art in Zambia does not come cheap and that a good part of its cost should have been invested by the artist in first class materials and appropriate workmanship. I can show embarrassing examples of Zambia’s top artists that belie this principle – usually because of sheer ignorance; sometimes because of irresponsible technical short cutting; or unfortunately, unavailability or expense of quality materials.

The following practical advice cannot take the place of a proper technical manual. But below is some advice that may help to improve matters in a simple way.

Get informed

There are numerous text books about each artistic discipline – but not or rarely available in Zambia. Zambian artists, however, do travel and should use such occasions to purchase technical books at art supply shops. They can also pull strings in the international network they often have or purchase on-line. There are two books I personally love and recommend to each artist. The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques by Ralph Mayer is a classic. Written in clear, largely non-technical English it is a must for any artist to read. Getten and Stout compiled Paintings Materials: A short encyclopaedia. This inexpensive Dover publication is more technical but equally indispensable when you need to quickly research any material used in art. And then, of course there is the I-net, the largest library in the world, accessible by now in almost all of Zambia. Once you get into it you won’t stop and you’ll ask yourself why you did not do your technical surfing earlier.

Get top grade materials

Worldwide each art tradition has its own standard material technology and so does each of the Western art media. The Western technologies, historically, are directed towards permanence of the work of art. Durability of the work of art is only achieved by the proper application of permanent materials. The VAC shop sells good materials and so does The Artshop at Zebra’s crossings cafe, both in Lusaka. But still you need to check on pigments and binders used.

Paper is the usual support for graphic art. The best paper is made of rags. Art paper is made by specialised paper mills. Buy one of those brands and get the kind suited to your medium. Good paper yellows little and takes printing ink, crayon, pencils, charcoal, water paint, tempera and gouache well. There are imitations of expensive pigments by cheap surrogates, and similarly you need to ensure that your oil paint is made of linseed oil.

Printing inks are a special concern. Note that offset printing inks and commercial silkscreen inks are not made to meet artistic standards as regards permanency. Most of these colours eventually fade. Simple test for fastness to light: take a piece of paper, apply ink or paint, cover one coloured half with paper and expose to sunlight by tacking to a window. Check after some weeks to observe changes. These can be dramatic.

Canvas. Canvas is the usual support for oil and acrylic paint. The only proper canvas is made of linen. In oil paint canvas is first sized with rabbit glue to protect the canvas from the deteriorating effect of (linseed) oil. Next the canvas is primed, formerly with a lead based white paint. Substituting the linen canvas for cotton entails a risk of “sagging” as the support in time loses its tautness. Skipping the sizing brings about the risk of the support being “eaten” by the oil and eventually breaking up. Using pva paint instead of rabbit glue and oil primer may result in disintegrating canvas and poor bonding between ground and paint. In short: if you want to paint in oil, use proper linen canvas as made by specialist factories and sold by specialist shops. Or paint on a wooden or Masonite panel. It appears that adequate support preparation is less critical in acrylic painting. Advised is to purchase canvas made for acrylic paint and apply acrylic primer. You can apply acrylic paint to a canvas prepared for oils but you may want to roughen its surface a bit by light fine sanding. This ensures better bonding.

Pigments and paints. In the western tradition there is a standard list of pigments for each medium – there is no space to reproduce such lists here. Do note, however, that different media and different supports all impose specific requirements on paints. Notably in murals the choice in colours is limited to those pigments that are resistant both to an acidic and an alkaline environment. Avoid the purchase of so-called student grade paints – they teach you wrong outcomes of apparently similar materials.

Fat over lean. Different pigments require different amounts of binder. In oil painting paints containing more oil should be applied over paint layers containing less oil – the leaner layers. Sinning against this principle causes constructional problems. An example of a fat paint is raw umber. These colours should only in lean mixtures be used in the underlying paint layers. The same principle applies to acrylic paint, but perhaps not so rigidly.

Use fresh paint. Use paint fresh from the tube and discard paint that has started to dry up on the palette. This applies especially to paints having binders that change irreversibly in the so-called drying process. These include the polymers (acrylics) and oils.

Thinners. Use appropriate thinner for the medium you are using. Do not use paraffin in oil painting. Mineral turpentine is good, natural turpentine better.

Storage and exposure. The work of art is subjected to environmental variables such as temperature, humidity, sunlight, wind, air born particles or gasses. Even a well-made painting may deteriorate if displayed or stored wrongly (see Witkamp, 2015). Generally store or display in a fairly dry place, avoid great fluctuations in temperature or humidity and be aware of bugs. Don’t expose 2-dimensional work to sunlight, same for wooden sculpture. Inform, if necessary, the buyer about appropriate preventive preservation measures. Prints, water colours and drawings should be properly framed (meaning: dust free, behind uv filtering glass, using acid free board and backing when exposed.

Notes

1 The author did research on makishi as part of his MA requirements. Copies of his Seeing Makishi have been deposited with The Livingstone Museum and the library of The University of Zambia (special collections).

2 The process of adopting western features by other societies sometimes has been labelled the ugly term “westernization,” as in Setti (2000, title page). This term suggests the changing of an indigenous cultural element by western influences. In our case there simply is no historical connection between most of these western techniques and a previous indigenous artistic practice. Diffusion therefore is a better term, though terms like acculturation and cultural interaction also apply.

About the author

The author is a cultural anthropologist with specialisations in non-Western art and anthropology of sub-Saharan Africa. He taught Materials and Techniques of Art part time at the Evelyn Hone College from 1977 to 1980 to students of the Art Teachers Diploma Course. He worked as a practising artist in Zambia from 1975 to 1980 and from 1988 till the present. Some of his writing can be accessed at various internet publication sites, including this one.

Bibliography

Arnheim, Rudolf. Visual Thinking. 1969. University of California Press.

Art and Visual Perception. 1974. University of California Press.

d’Azevedo, Warren L. The Traditional Artist in African Societies. 1989. Indiana U.P.

Boas, Franz. Primitive Art. 1955 New York, Dover. First published in 1927.

Ellison, Gabriel. Art in Zambia. 2004. Lusaka, Bookworld Publishers Ltd.

Gettens, Rutherford J. and George L. Stout. Painting Materials. 1966 New York, Dover

Publications. First Published in 1942 by D. Van Nostrand Company Inc.

Lusaka National Museum. Lusaka National Museum Art Catalogue. 2001.

Ralph Mayer. The Artist’s Handbook of Materials and Techniques. 1982. New York, The

Viking Press.

Schneider, Allen M. and Barry Tarshis. Physiological Psychology.1975. New York,

Random House.

Setti, Godfrey. An Analysis of the Contribution of Four Painters to the development of

Contemporary Zambian Painting from 1950 to 1997. 2000. Manuscript, M.A. research

essay, Rhodes University.

Witkamp, Gijsbert. Seeing Makishi. 1988. M.A. thesis and research report.

Photocopied manuscript. State University of Leiden. Copies at University of

Zambia and Livingstone Museum.

Keeping Art. 2015. Z-factor technical bulletin no 1. Accessible as I-net publication

at: http://artblog.zamart.org/2013/08/caring-for-your-art-work-prints.html